Controlled Substance lists and chemical families

Controlled Chemical families and Generic statements

In this blog post I’ll explore a little more on how you can address the requirements of Controlled Drug laws globally which often control areas of chemical space in an effort to control “legal highs” alongside more traditional lists of controlled substances

This is part our blog series on how to easily check if your chemicals are regulated under controlled Drug laws, with examples from the USA & UK, although we cover over 30 countries.

In an effort to avoid “legal highs” where a small chemical change is made to a molecule to technically take it out of control, but retain its narcotic effect, legislators often choose to control entire chemical families of similar molecules. These are often know as generic statements, markush rules, or chemical family based controls. Some legislators also talk about analogues, a definition which is deliberately vague. However generic statements are very precise (although complicated) in defining what chemicals are controlled or not, making prosecution easy while also meaning companies can be sure what is and isn’t regulated.

The underlying approach originally came from patents, whereby chemists would define not just the chemical to be patented, but also all closely related chemicals, by defining R-groups on a core, where R could be a defined number of chemical modifications.

This approached was first used for controlled drugs in the UK in 1971 and the Misuse of Drugs Act. Since then it has widely been used both in the UK and also countries globally, including the USA, Canada, China, Germany, France, Switzerland, Belgium and international conventions such as a the Chemical Weapons convention and Montreal protocol on Ozone depleting chemicals.

Indeed in the UK, you will not find Ecstasy (MDMA) named in the legal schedules (only advisory lists of commonly encountered drugs). Instead its controlled under a ‘generic statement’ relating to phenethylamines added to the United Kingdom’s Misuse of Drugs Act in 1977. This definition states;

‘any compound structurally derived from phenethylamine an N -alkylphenethylamine,a-methylphenethylamine, an N -alkyl-a-methylphenethylamine,a-ethylphenethylamine, or an N -alkyl-a-ethylphenethylamine by substitution in the ring to any extent with alkyl, alkoxy, alkylenedioxy or halide substituents, whether or not further substituted in the ring by one or more other univalent substituents’

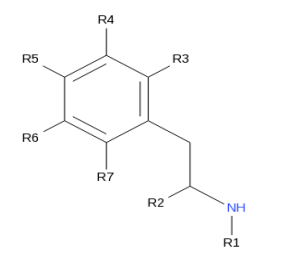

This converted into chemical notation looks like

R1 = an alkyl group (alkyl itself is a chemical family, not a single thing).

R2 = a methyl or ethyl group.

R3 to R7 inclusive = alkyl, alkoxy, alkylenedioxy or halide substituents, whether or not further substituted in the ring by one or more other univalent substituents.

In the UK alone there are several dozen of these, of which the one above is probably the simplest. Globally there are several hundred of these.

Within the USA, ‘Fentanyl like chemicals’ and ‘synthetic cannabinoids’ are covered by these generic statements. An example of which is below (the full wording is available here)

Fentanyl-related substances means any substance not otherwise listed under another Administration Controlled Substances Code Number, and for which no exemption or approval is in effect under section 505 of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act [21 U.S.C. 355], that is structurally related to fentanyl by one or more of the following modifications:

- A) Replacement of the phenyl portion of the phenylethyl group by any monocycle, whether or not further substituted in or on the monocycle.

- B) Substitution in or on the phenylethyl group with alkyl, alkenyl, alkoxyl, hydroxyl, halo, haloalkyl, amino or nitro groups.

- C) Substitution in or on the piperidine ring with alkyl, alkenyl, alkoxyl, ester, ether, hydroxyl, halo, haloalkyl, amino or nitro groups.

- D) Replacement of the aniline ring with any aromatic monocycle, whether or not further substituted in or on the aromatic monocycle.

- E) Replacement of the N-propionyl group by another acyl group.

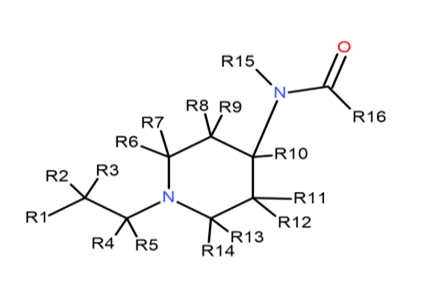

Which when converted into chemical search notation looks like this

R1 = substituted or unsubstituted phenyl or another monocycle.

R2-R5 = alkyl, alkenyl, alkoxyl, hydroxyl, halo, haloalkyl, amino, nitro.

R6-R14 = alkyl, alkenyl, alkoxyl, ester, ether, hydroxyl, halo, haloalkyl, amino, nitro.

R15 = substituted or unsubstituted phenyl or another aromatic monocycle.

R16 = any substituent, including hydrogen.

How can you easily check if your chemical falls within one of these statements?

Obviously, it is very complicated to check just these few examples against 1 chemical, let along the hundreds of other generic statements and if you have hundreds or thousands of chemicals to check. Fortunately there is a simple way to do it. Controlled Substances Squared by Scitegrity already encode all these statement, plus named drugs, analogues and more to allow you to easily check if your chemical is controlled by entering a name or chemicals structure (smiles, .mol, inchi, drawn etc).

Trusted by our Clients